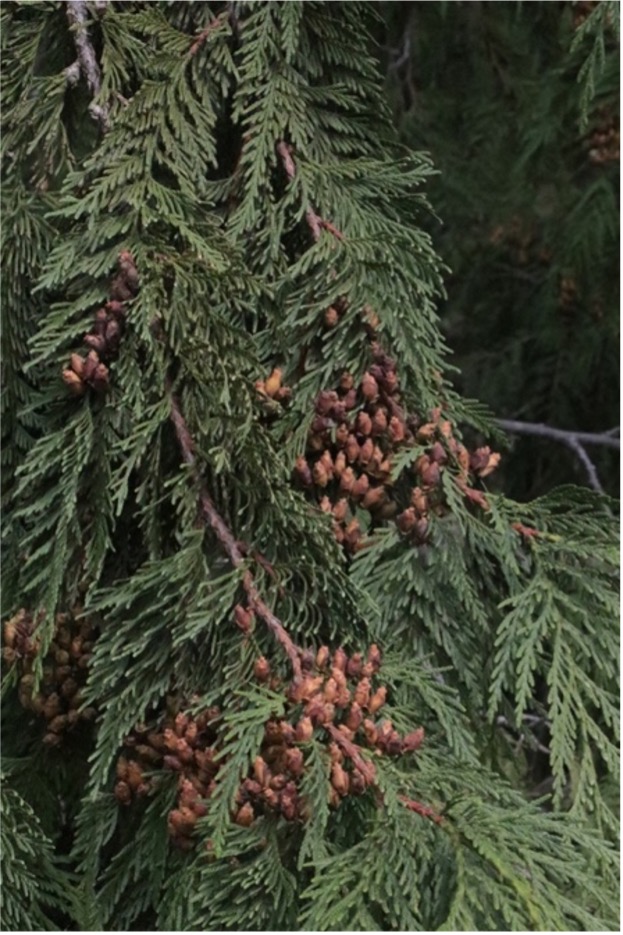

Tree of Life (Thuja plicata)

November 28, 2024

Western red cedar (Thuja plicata) is a charismatic, colossal conifer that can be found in the Pacific Northwest between Northern California and Southern Alaska. A member of the Cupressaceae family, it is related to other impressive conifers like coast redwoods (Sequoia sempervirens), giant sequoias (Sequoiadendron gigantea), incense cedars (Calocedrus decurrens), cypress (Cupressus spp.), and junipers (Juniperus spp.). Despite being colloquially known as a cedar, however, it is not related to true cedar trees (Cedrus spp.) which belong to the Pinaceae family and are not native to North America. This confusing moniker motif continues with incense cedars; Calocedrus translates to “beautiful cedar” but again, this beautiful “cedar” is of no relation to true cedars. The word cedrus has roots in both Latin and Greek languages. The name is thought to have been functionally applied to trees in the New World that have similarly aromatic wood, such as Thuja and Calocedrus, long before botanical taxonomists were able to disentangle discrete genetic lineages.

Hence a misleading modern nomenclature of cedars. However, long before common names were applied to botanical epithets by Western settlers, Native American tribes such as the Kwakwaka’wakw people of Vancouver Island have embraced, celebrated, and depended upon Western red cedar as the Tree of Life for more than 9,000 years.

This iconic tree is easily earmarked by its aromatic essence. The smell of crushed needles is said by some to be evocative of pineapples, producing a pleasant-smelling salve. In addition to satisfying the olfactory senses, the medicinal benefits of Thuja plicata leaves are plentiful, including treatment for rheumatism, coughs, tuberculosis, and fevers. It is also anti-microbial, anti-fungal, and anti-bacterial.\

The wood and bark are also emblematically pungent. There are a number of chemicals responsible for creating these scents, which contribute to the innumerable properties of this species. To name a few: plicatic acid, methyl ether, thujaplictins, thujaplicinol, thujic acid, methyl thujate, and many others. You may have noticed that these chemical compounds share etymology (word origins) with Thuja plicata, which is not accidental; they are endemic to the heartwood and bark of Western red cedar.

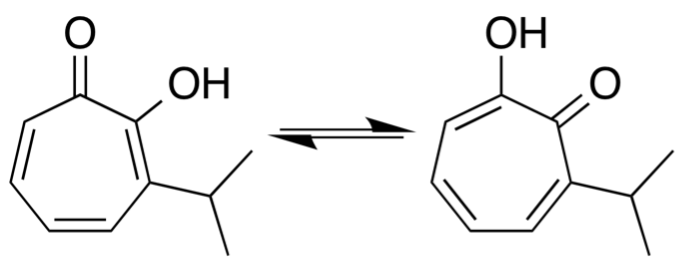

Thujaplicins (the molecule depicted to the right) are produced by mature Western red cedar trees and serve as natural fungicides which preclude the wood from rot/decay and make them a prized rot-resistant lumber. They also suppress enzymatic browning, which means that chemicals produced by this tree can be extracted and applied to other things (such as vegetables, fruits, mushrooms and seafood) to prevent darkening. The pesticidal and insecticidal properties elicited by these chemicals have sparked academic interest in the agricultural world, providing potential ameliorations to plant disease management and postharvest decay.

Another chemical compound, called thujaplicinol, is found in the bark, needles and xylem of Western red cedar. Thujaplicinol is extracted as a phenolic component of essential oils, and also possesses antifungal and antibacterial properties. Becoming of interest to experimental modern medicine, it is also an anti-tumor agent, and has been shown to have high cytotoxic effects on several cancers, including stomach cancer, lymphocyctic leukemia, and estrogen-dependent breast cancers.

These magical medicine trees can grow to become massive, using a shallow root system to support large buttresses and towering trunks. The largest known Western red cedar in the world lives in the Olympic National Park and is named Kalaloch Redcedar. It has a circumference of more than 61 ft and is thought to have germinated in the year 450 AD (± 200 years), making it around 1,577 years old.

The significant chemical properties aforementioned contribute to the incredible usefulness of Western red cedars. Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest make the most of this rot resistant tree by creating canoes, totem poles and tools with the wood. The bark serves use as a natural fiber, crafting items such as rope, baskets, clothing and hats. Arborvitae is deeply revered by coastal tribes, providing cultural, physical, and spiritual sustenance.

I leave you with a Coast Salish legend of the origin of the Red Cedar, told by Bertha Peters and published in the wonderful book, Cedar: Tree of Life to the Northwest Coast by Hilary Stewart,

“There was a real good man who was always helping others. Whenever they needed, he gave; when they wanted, he gave them food and clothing. When the great Spirit saw this, he said, ‘That man has done his work; when he dies and where he is buried, a cedar tree will grow and be useful to the people – the roots for baskets, the bark for clothing, the wood for shelter’.”

Article originally written for Wild & Wise Herbal CSA, 2024 Fall CSA Newsletter

Wavy Leaved Silk Tassel (Garrya elliptica)

July 23, 2024

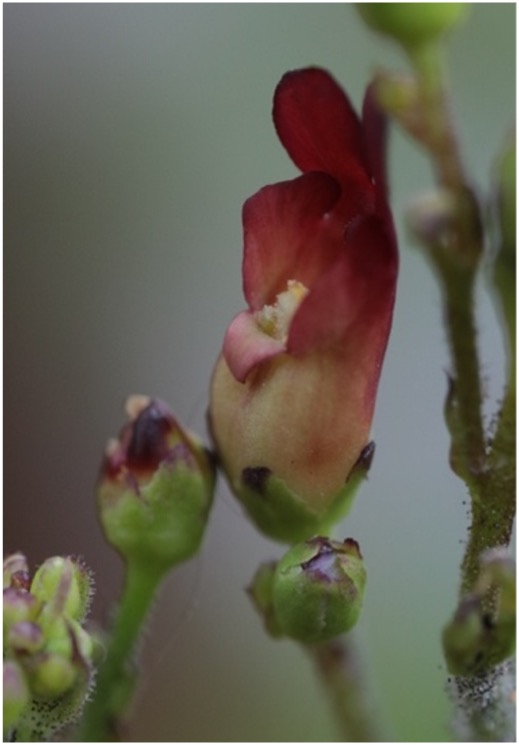

If ever there was a stigma that native plants possess a lackluster display of beauty and elegance, wavy leaved silk tassel (Garrya elliptica) would prove it wrong. Blooming in the late winter, the charismatic, cascading catkins are one of the first flowers to celebrate the slow return of the sun.

Garrya is a genus of flowering plants belonging to the family Garryaceae. Their native range includes the Western United States, Mexico, Central America, and the Greater Antilles. In total, there are 18 species of Garrya, five of which occur in California. The species of Garrya that is featured in this season’s Wild and Wise CSA package, G. elliptica, is rather restricted in range to the coastal ranges of Southern Oregon and Northern California, where it is only found within 20 miles of the Pacific Ocean. It is associated with coastal sage and chapparal, Northern coastal scrub, Mixed evergreen coastal forest, and Northern coastal sage scrub ecotypes.

Silk tassels are dioecious, meaning that male and female parts occur on different individuals. The male catkins release abundant volumes of bright yellow pollen from their almost-pink velvety flowers. This pollen is carried by the wind, and if luck is the air, the pollen will find a female silk tassel flower. The female flowers are concealed within the catkins by what look like reddish eyelashes. Once pollinated, the female flowers will slowly develop into a long chain of fuzzy fruits, each containing two seeds.

It is the male flowers that are sure to capture the curious eye, as they drape down with tinsel-like elegance fit for a ceremony. In fact, nurseries have been cultivating wavy leaved silk tassel cultivars since as early as 1842. One of these cultivars, known as ‘James Roof’, dons especially spectacular catkins (>12” long), and has been the awarded the prestigious Award of Garden Merit by the Royal Horticultural Society.

Though the flowers are wind pollinated (which is the common syndrome for most flowers borne in catkins), the early season nectar source undoubtedly captures the attention of bees, who are drawn to the vestigial nectary on the male flowers of silk tassel.

As noted earlier, wavy-leaved silk tassel produces up to two seeds per fruit. These seeds are encased in a gelatinous goo, which is called the sarcotesta and aids in seed dispersal (to provide another example of a seed with a sarcotesta, it’s the yummy part of a pomegranate seed). As the fruit reaches maturity, the sarcotesta will dry out, turning a deep red and then black color. At this stage, the fruits can be squeezed to readily release the seeds from their hairy pods. When re-exposed to water, the sarcotesta will rehydrate. It is important to keep the seeds hydrated for successful propagation – and this can be a formidable venture, as it may take up to two years before the seeds actually germinate. If the showy male flowers are what you’re after, you’ll have to wait a few more years to see a sex-determining bloom on your baby Garrya seedling – which is why many nursery propagators prefer cuttings. If you’re growing for medicinal purposes, the sex is irrelevant, and if you’re growing for restoration purposes or to encourage prolific progeny of this plant, be sure to plant both sexes on site.

The name Garrya comes from a man named Nicholas Garry, who was the secretary of Hudson’s Bay Company in the early 1800’s. Garry was an assistant to David Douglas, a notable Scottish botanist that described many plants in the Pacific Northwest, including Douglas-fir, Pseudotsuga menziesii. The name elliptica describes the shape of the leaf, meaning ‘about twice as long as broad’, or ‘elliptic’.

The traditional and medicinal uses of silk tassel are sundry. Some tribes, such as the Pomo and Kashaya, have utilized an infusion of the leaves to invoke a woman’s period. Others use a tea from the leaves to treat colds, stomachaches, and as a laxative. Here in Northern California, members of the Yurok Tribe harden the wood of Garrya elliptica with fire and use the sticks as a tool to pry mussels off rocks.

Article originally written for Wild & Wise Herbal CSA, 2024 Summer CSA Newsletter

Water Fern (Azolla filliculoides)

There are various native plant species that cover the surface of stagnant or slow-moving water. One of these species is called water fern (Azolla filiculoides). Not to be confused with algae, Azolla is an aquatic vascular plant with a very shallow root system that grows on the water surface rather than in the water column. True to its name, it is a type of fern. Typically, the plant is bright or dark green, making the water appear to be covered in “pond scum”, but this plant is anything but scum. As a stress reaction, Azolla can turn a deep red-amber color, appearing dead or dormant. Despite the discreet and unassuming nature of this unusual plant, it has some mind-blowing properties, including the ability to purify water and fix nitrogen.

Nitrogen is often a limiting nutrient for primary producers because atmospheric nitrogen (N2) is not readily utilized by plants. As a result, many plants (such as those in the pea family, Fabaceae) have evolved the ability to “fix” nitrogen by converting it to an accessible form of nitrogen (NH4+). Some plants do this with the help of bacterial partners, as is the case with red alder (Alnus rubra) and specific bacteria, which partner to produce root nodules. In return for providing a home, the actinomycetes share some of their usable nitrogen with the red alder. While this activity occurs in the roots of the host plant, excessive nutrients are leaked into the surrounding environment, thus providing bioavailable nitrogen to other plant species and improving soil fertility within the red alder ecosystem. Instead of partnering with a bacteria like red alder does, Azolla has a symbiotic relationship with a blue-green algae species called Anabaena azollae. The Anabaena is housed within the leaves of Azolla, and in return, Azolla receives fixed nitrogen which is ultimately shared with the surrounding environment.

In addition to being able to contribute nutrients to the environment, Azolla has the ability to uptake metals as well as organic and inorganic pollutants from water. This process, known as phytoremediation, can take place via 4 different mechanisms. I’ll exclude the chemistry details here, but the important takeaway is that this little plant can extract toxic pollutants from water. Researchers are investigating the use of this plant in wastewater treatment facilities. There are countless more benefits and potential applications of Azolla to modern human civilization – including the potential to split water molecules and create energy. Azolla is endlessly interesting.

So how does this little plant affect our ecology here along the Trinity River? By covering slower moving bodies of water like ponds and backwater areas, it helps regulate water temperatures and provides habitat for cover-loving species. By the same mechanism, it also decreases habitat for mosquitos. It also serves as a food source for a wide variety of wildlife, from western pond turtles to waterfowl. These properties, combined with the ability to fix nitrogen and remove pollutants from water, make this easily over-looked water fern an important constituent of riparian and aquatic habitats.

Article originally written for the Trinity River Restoration Program newsletter, The River Riffle

Figworts and Platypuses

July 5, 2023

Figwort, also known as California bee plant or by its scientific name, Scrophularia californica, is a common Northern California native wildflower. It occupies wet niches and forest edges and can be found growing throughout western North America, from British Columbia to Baja California. The quaint, small flowers are easily overlooked by an unobservant passerby, but not by pollinators, who are attracted to the blooms in bounty throughout the mid-spring to mid-summer.

Figwort can be identified by having tall (80-120 cm), squarish stems. The triangular to oval shaped leaves lie directly opposite each other, growing smaller in size moving up the stem. The edges of the leaves are notably toothed. At the top of the stem, a spread out spattering of small red flowers branches out. The flowers have an upper lip with two lobes (which curl over the opening of the flower), and a lower lip with three lobes. The top of the flower is deep red, gradually becoming paler towards the bottom of the flower to an almost yellowish creamy white. The entire corolla (flower) is cradled by a green, five-lobed calyx.

Pollinators habitually use color to direct them towards tasty flower nectar treats. Brown flowers are often pollinated by flies, white flowers are often targeted by moths and bats, and red flowers are favored by hummingbirds. Bees cannot see the color red (which is why they are typically drawn to blue, purple, and yellow flowers), but they are attracted to bright colors, pretty patterns, and fragrant aromas. Based on this information, which pollinator do you think visits figworts?

Hummingbirds are probably the primary pollinator for this species, but true to its common name, a patch of California bee plants is guaranteed to be a buzz for local bees. As the bees aren’t using the red color to identify figwort flowers as fitting food, there are several other ecological mechanisms to encourage the bees to make a worthwhile stop. The simplest of these is smell; the aromatic nectar is within the tube of the flower and serves as an attractant for all types of pollinators. Another method is with ultraviolet nectar guides, which are invisible to the human eye but provide bees with a landing runway towards their nectar prize. Perhaps the most interesting method that bees utilize to locate these flowers is by electroreception.

Electroreception is a fancy word that describes the ability for an organism to identify external electrical forces. Every living critter generates an electrical signal from activity within the muscles and nerves. Many aquatic animals, such as fish and amphibians, have special receptors to detect this bioelectric field, which are used to locate and hunt prey. This is a particularly helpful adaptation in low visibility conditions. Platypuses baffled scientists in the early 1800s by hunting in the depths of freshwater bodies without the use of sight, smell or sound. It wasn’t until many years after discovering the enlarged neural network within platypus bills that scientists discovered an associated network of electroreceptors. In other words, the strangely unique bill of a platypus is adapted to detect the electrical signals of prey, thus enabling deep water hunting opportunities in conditions with no visibility. Another aquatic critter that utilizes electroreception are dolphins. Different from echolocation, which is how dolphins use sonar to detect prey, some dolphin populations have been found with visible electroreceptors (which have gel-like mucus to help conduct electrical signals), indicating that they also use electric signaling to locate food.

Much like platypus and dolphins, bees can utilize electroreceptors to identify electrical signals produced by flowers. This is slightly more complex than aquatic electroreception; because air is less conductive than water, bees must be able to detect the very weak electrical field associated with flowers. They do so via mechanosensory hairs on top of their heads between the antennae, which deflect in the presence of electric fields and send neural responses to the central nervous system. Bumblebees can use this information to discriminate between rewarding stops and un-rewarding stops, training themselves to associate certain combinations of colors and electrical frequencies with specific rewards. Honeybees, on the other hand, use their electroreceptors to communicate with other members of the hive in something called a “waggle dance”. During the waggle dance, the vibrating forager produces electrical stimuli, which is received by other honeybees to convey forage information.

In addition to making honeybees dance, figwort chemistry causes caterpillars to coalesce. The plant contains iridoid glycosides that are toxic to most vertebrates. Most generalist butterfly species are deterred by the toxic compounds, but several specialist butterflies have adapted to not only circumvent the toxicity, but also to utilize it to their advantage. By using California bee plant as a host plant, specialized caterpillar species can metabolically sequester these iridoid glycosides, becoming poisonous to predators. So, when a hungry bird swoops down for a tasty caterpillar snack and realizes the wriggler is laden with nasty and toxic compounds, the caterpillar gets to live another day and the bird goes home hungry. Amazingly, the caterpillar continues to carry around these compounds into butterfly adulthood, protecting itself with an unpalatable cloak of chemicals.

On a larger, more anthropogenic scale, the chemicals within figwort have served medicinal purposes since time immemorial. Native Americans have developed a long-term relationship with this plant as poultice, wash and tea, which can elicit sedative, astringent, diuretic, and antifungal properties. The European cousin of this species, Scrophularia nodosa, is used for various skin disorders and detoxification. In fact, in the 1400’s, the genus of this plant (Scrophularia) was named after “scrophula”, which is a tuberculosis related disease affecting the human lymph nodes which S. nodosa has been used to treat.

California bee plant is readily propagated by seed and tends to re-seed itself abundantly in our coastal Californian environment. To gather seed, wait until the seed husk turns papery and brown. Try gently rattling the stem to hear ripe seeds shaking within the seed husk, or break one open to look for the shiny, black seeds. Store in a paper bag for no more than two years, as viability starts to soon decline. Direct sow outside and cover with a small amount of soil (less than ½”) at the beginning of the seasonal Fall winter rains or start in flats in a greenhouse in early spring.

Article originally written for Wild & Wise Herbal CSA, 2023 Summer CSA Newsletter